|

Overview

-

3Patient

Assessment-Estimating the extent and basis of patient anxiety

-

Psychological factors to consider

-

Appropriate levels of fear-the

anesthesia provider may help set the patient's expectations:

-

Presurgical explanations should

take into account the anxiety-state of the patient, i.e. a

very anxious patient may have even further anxiety as a result

of such discussions

-

Anesthesia providers may aid

the patient in coping with preoperative anxiety by suggesting

that patients focus their attention to other more pleasing or

at least distracting activities

-

Examples of effect of coping

mechanisms which can be promoted by the anesthesia provider

-

Helping the patient view

themselves as part of rather than separate from the

health-care providing team. This type of

"empowerment" reduces the likelihood of the

patient regarding himself as an "victim" and can

help the patient recognize their role in the

decision-making process that led to surgery

-

The anesthesia provider may

help the patient assume a level of control concerning

their environment and situation-for example use of

breathing control in promoting relaxation. Providing

opportunities for control may be especially important for

children and young adolescence -- for example allowing a

child to choose on which finger the pulse oximeter is to

be placed would be such an example

-

Relaxation methods: The

anesthesia provider may suggest contraction/relaxation

cycles of muscles in a small region, such toes or

ankles

-

Mental

distraction-such music, selective attention,

etc. approaches which promote relaxation may be

useful.

-

Time of administration: 1-2 hours

before anesthesia induction

-

Outpatient setting: IV

premedication just before surgery

-

Primary goals for premedication (premedication

agents may include antihistamines, antiemetics, alpha2

adrenergic receptor agonists, antacids, histamine receptor (H2)

antagonists, opioids, benzodiazepines, gastrointestinal

stimulants)

-

Anxiolytic effects -- reduction

in patient anxiety with expected reduction in

circulating catecholamines

-

Sedation

-

Reduction in preoperative pain

(analgesic effect)

-

Amnesia-the use of an amnestic

agent is common with midazolam (Versed) often employed.

Midazolam (Versed) belongs to the benzodiazepine category of

drugs

-

Reduction in secretion --

antisialagogue effect

-

Increase in gastric fluid pH

with a decrease in gastric fluid volume-these effects are

designed to reduce risk which may be associated with

aspiration

-

Reduction of autonomic

nervous system reflex responses-To accomplish this effect

sometimes antimuscarinic agents are used in as a consequence

surgical stimulation of muscarinic receptors are less likely

to provoke adverse cardiac effects (e.g. bradycardia,

arrhythmias)

-

Reduction in required

anesthetic amounts -- Premedication with sedative-hypnotic

agents and/or opioids to reduce the amount of anesthetic

required to achieve a given level of anesthesia. The

advantages may include more rapid emergence upon completion of

the case

-

Prophylaxis with respect to allergic reaction (e.g. antihistamines may be helpful)

-

Additional premedication issues:

-

Reduced cardiac activity (e.g.,

an anticholinergic drug such as atropine may prevent

bradycardia associated for example with surgical-induced

stimulation of muscarinic receptors). To manage cardiac vagal

activity, antimuscarinic agent should be administered DURING

surgery, just prior to the expected need or in response to

vagal stimulation

-

Reduction/avoidance of

postoperative nausea and vomiting-facilitated with I. V.

antiemetic drug administration JUST PRIOR to awakening (this

approach is probably better than waiting for symptom

developments and then treating the nausea)

-

Postoperative analgesia may be

best approached by use of IV opioids or neuraxial opioids JUST

PRIOR to symptom development-here administration may be

best provided just before awakening or just before a painful

surgical action

-

Circumstances in which

sedative-hypnotic (depressant) or some other pharmacological premedication would

be warranted:

-

Cardiac surgery

-

Cancer surgery

-

In the presence of pre-existing

pain

-

Regional anesthesia

-

Some circumstances in which

sedative-hypnotic (depressant) pharmacological premedication would

NOT be warranted:

-

In the hypovolemic patient

-

In the presence of significant,

severe pulmonary disease (additional respiratory depression

associated with sedative-hypnotics would be ill-advised)

-

Intracranial pathology

-

Reduced level of consciousness

-

Probably not in elderly

patients

-

Newborns (< 1 years of age)

-

Factors that influence the choice

those drugs for premedications and associated dosages

-

Whether the surgery is

classified as "inpatient" or "outpatient"

-

Whether the surgery is being

performed as an elective or emergency procedure

-

Concerns about the ability of

the patient to tolerate the drug

-

Patient age

and weight and

physical status

-

Anxiety level of the

patient-Recall that an anxious patient is likely to have

elevation of circulating catecholamines which may cause a

suboptimal cardiovascular preoperative state

-

Whether the patient has had an

adverse response to the particular medication during a

previous procedure-This consideration emphasizes how important

an adequate history or chart review is in deciding medication

choice.

Benzodiazepines

-

Overview:

-

Most commonly used sedative/anxiolytic

-

Anxiolytic effectiveness is

observed at dosages which do not result in cardiopulmonary

depression or excessive sedation

-

Certain benzodiazepines also

exhibit significant anterograde amnesia (amnesia subsequent to

drug administration).

-

Examples of these benzodiazepines

include midazolam (Versed) and lorazepam (Ativan).

-

These

agents may also cause, on predictably, some degree of

retrograde amnesia as well.

-

Benzodiazepines may also be

used the night before schedule surgery in management of

pre-surgical insomnia-- examples include lorazepam (Ativan),

temazepam (Restoril), and triazolam (Halcion)

-

Sometimes benzodiazepines used

pre-surgically can result in prolonged and excessive

sedation. Patients receiving lorazepam (Ativan) at high

dosages (total dose > 4 mg orally at 5 ug/kg) may be most

susceptible to this excessive sedation.

-

Intramuscular injection of

diazepam (Valium) may be painful because diazepam (Valium) is

dissolved in the irritating solvent propylene glycol;

intramuscular injections of midazolam (Versed) does not cause

local irritation since the chemical characteristics of

midazolam (Versed) do not require the use of propylene glycol

as a solvent (an aqueous solvent is used)

Adverse Effects: benzodiazepines

-

Major adverse effects

-

Inpatient considerations:

-

Outpatient considerations:

-

Factors/conditions which

increase likelihood of preoperative excessive sedation

associated with the use of benzodiazepines and other

sedative hypnotics:

-

Infancy, advanced age

(elderly patients), chronic debilitating disease or

malnutrition, pregnancy, renal dysfunction, hepatic

dysfunction, pulmonary dysfunction, adrenal insufficiency,

myasthenia gravis, myotonia, sickle cell disease, acute

drug/ethanol intoxication5.

3Comparisons: midazolam

(Versed), diazepam (Valium), and lorazepam (Ativan)

| |

Midazolam

(Versed) |

Diazepam

(Valium) |

Lorazepam

(Ativan) |

|

Dosage

(oral) |

0.3-0.5

mg/kg |

0.15-0.2

mg/kg |

0.015-0.03

mg/kg |

|

Time

to peak effect |

thirty

minutes-60 minutes |

1-1.5

hours |

2-4

hours |

|

Duration |

1-2

hours |

2-2.5

hours |

4-6

hours |

|

Elimination

halftime (time to reduce drug concentration by 50%) |

1-4

hours |

20-100

hours (includes active metabolites) |

8-24

hours |

|

Apparent

volume of distribution (Vd) |

1.1-1.7

L/kg |

0.7-1.7

L/kg |

0.8-1.3

L/kg |

|

Presence

of active metabolites |

yes,

but relatively weak in effect |

prominent |

none |

|

Metabolic

mechanism |

hydroxylation

and conjugation |

hydroxylation

and conjugation |

conjugation;

conjugation reactions are less likely to be affected by age or

the presence of hepatic disease |

|

Clearance |

6-11 ml/kg per

minute |

0.2-0.5 ml/kg

per minute |

0.7-1 ml/kg per

minute |

|

Lipid

solubility |

high |

high |

intermediate |

|

Effect

of age |

in

the elderly, midazolam (Versed) half-life may be increased by as

much as eight hours |

in

the elderly the half-life of diazepam (Valium) may be increased

by several days |

|

|

-

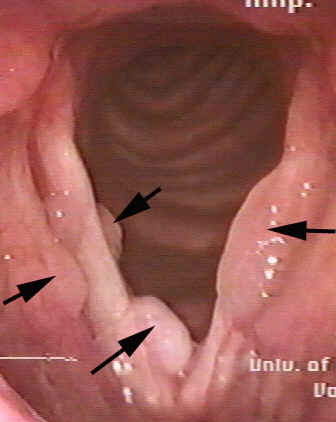

"The arrows point to multiple papilloma growths on the larynx caused by a viral infection. Permission to

reproduce

photo courtesy of the University of Pittsburgh Voice Center-

-

(Ed. note: This is a photograph that shows how laryngeal papillomatosis--RRP of the larynx--does not invariably

present with a traditional cauliflower-appearance.)"

|

|

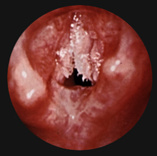

Papillomatosis

-

From On-Line Airway Atlas 2000,

John Sherry, II, M.D © 1999,2000

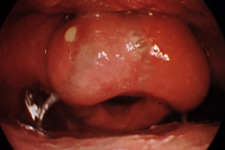

Epiglottis (with Abscess)

-

From On-Line Airway Atlas 2000 ,

John Sherry, II, M.D © 1999,2000

|

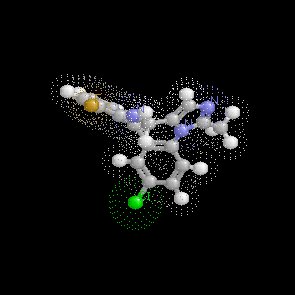

Benzodiazepine

pharmacology

|

Diazepam (Valium) |

Midazolam (Versed) |

1Opioids

-

Overview

-

Advantages

for use in preoperative medication:

-

Absence

of myocardial depressant effects

-

Alleviate

the preoperative pain

-

Management

of discomfort associated with invasive monitor insertion

-

Management

of pain which may be associated with establishing regional

anesthetia

-

Preoperative

opioids may limit or eliminate the need for supplemental

analgesics during the early postoperative phase

-

Generally, in the absence of preoperative pain there may

be no compelling reason to include a narcotic for

preoperative anesthetic medication.

-

Commonly

used opioids for premedication

-

Contexts

for opioid administration:

-

Intramuscular: appropriate for

nitrous oxide-opioid anesthesia

-

Intravenous administration:

appropriately administered immediately before induction (fentanyl

(Sublimaze) is a good choice in this application)

-

Pain associated with

regional anesthesia or associated with invasive monitoring

catherization or even large intravenous lines may justify

treatment with preoperative opioids.

-

As would be expected

for many agents, dosage reduction may be required for the

elderly patient.

-

Elderly patients may have

reduced pain sensitivity that may exhibit an enhanced analgesic

response to the opioid

-

Occasionally preoperative opioids

are administered in advance of a nitrous oxide-opioid

anesthesia plan -- the rationale is that previous opioid

administration allows the anesthesia provider to gauge the

patients ensuing intraoperative opioid response.

-

For postoperative pain,

preoperative opioids may be employed; however, it is

probably preferable to either provide administration in to

recover room setting or perhaps most appropriately provide

IV opioids during the emergence

-

Preoperative opioid

administration may lower anesthetic requirements

-

For facemask induction,

opioids may be used in combination with other agents-in this

case opioid-mediated respiratory depression may decrease

ventilation during spontaneous breathing which will reduce

the rate of inhalational drug uptake. {the circumstance

might arise if for some reason intravenous induction agents

may not be used}

-

Adverse Effects:

-

Minimal cardiovascular effects

are noted, except for high-dose meperidine (Demerol)

-

Respiratory depression: associated with reduced responsiveness

to CO2 (medullary respiratory center

depression)

-

Orthostatic hypotension secondary to peripheral vascular smooth

muscle relaxation:

-

Opioids prevent the expected compensatory

peripheral vascular vasoconstriction.

-

This effect is in

addition to opioid- promoted histamine release that tends to

cause a hypotensive reaction.

-

The hypotensive response will be more

profound in patients who are hypovolemic.

-

Hypotensive reactions

can be avoided by ensuring that patients remained supine

following opioids (and other) premedication agents.

-

Nausea

and vomiting: These effects are frequently associated

with opioid administration, possibly occurring as a result of stimulation

of the medullary chemoreceptor trigger zone or vestibular

apparatus stimulation leading to motion sickness.

-

The likelihood of nausea

and vomiting may be reduced by placing the patient in a

recumbent position; however, the use of opioids because of

their tendency to cause nausea and vomiting perhaps should be

avoided in the same-day outpatient setting or if the

surgical procedure's themselves are likely to cause nausea

and vomiting {i.e. some gynecological and opthalmological

surgeries}

-

Delayed gastric emptying, which is associated with nausea

symptoms, has two important consequences-(1) altered absorption

rate for orally-administered agents and (2) and increased

risk of pulmonary aspiration

-

Opioids may also cause smooth muscle constriction (biliary spasm

{choledochododenal sphincter spasm, i.e. sphincter of Oddi}).

Manifestation consists of an upper right quadrant pain secondary

to smooth muscle constriction

-

Patients with

biliary tract disease should perhaps not receive opioids.

-

Also pain associated with biliary spasm, e.g. caused by an

opioid, may be difficult to distinguish from angina particularly

since pain from either angina or biliary spasm would be relieved

by smooth muscle relaxation due to sublingual nitroglycerin.

-

Opioid-induced pain, however, would be relieved by

administration of a pure opioid antagonist such as naloxone (Narcan)

or naltrexone (ReVia) or possibly glucagon. These drugs would not reverse true

anginal pain.

-

Meperidine (Demerol) is less

likely than morphine to cause biliary tract spasm.

-

Pruritis-probably secondary

to histamine release;

-

Accordingly opioids may cause flushing and

dizziness.

-

Since opioids are miotic

agents, pinpoint pupils may occur.

-

Specific agents:

-

Morphine:-

dosage (5-15 mg, IM Route of Administration)

-

Well absorbed following IM

administration

-

Time to onset: 15-30 minutes

with peak effect at about 45-90 minutes with total duration

of action as long as about four hours

-

Side reactions as noted for

the opioid group in general, including ventilation

depression; orthostatic hypotension as well as nausea and

vomiting secondary to effects on the chemoreceptor trigger

zone (CTZ) or on the vestibular apparatus

-

Reduction in GI motility

-

Preoperative use of morphine

reduces cardioacceleration associated with surgical

stimulation and volatile anesthetic agents

-

Meperidine

(Demerol) dosage: (50-150 mg, IM Route of Administration)

-

Less potent compared to

morphine (about 10% as potent)

-

Route of Administration: oral

or parenteral

-

Single dosage effect

duration: 2-4 hours with intramuscular injection providing a

variable time to peak effect and duration

-

Elimination: mainly through

hepatic metabolism

-

Cardiovascular effects:

positive chronotropic effect secondary to antimuscarinic

drug effects.

-

Fentanyl (Sublimaze):dosage-1-2

ug/kg intravenous for preoperative analgesia

-

Agonist-antagonist agents

-

These drugs, e.g. pentazocine

(Talwain), butorphanol (Stadol), nalbuphine exhibit reduced

respiratory depression compared to pure opioid agonists;

however, these drugs also have comparatively limited

analgesic effects.

-

These partial agonist,

given preoperatively, reduce the efficacy of pure opioid

agonist given postoperatively to control postoperative

pain. Partial agonist administration can in fact

limit or reverse analgesia caused by the presence of the

pure agonist

-

4Side effect incidence

following preoperative opioid administration: [1 hr following

dosage]-- original citation: Forest, w.H.,

Brown, B.W. et al.: "Subjective responses to six common

preoperative medications", Anesthesiology 47:241, 1977.

References:

-

1Preoperative Medication in

Basis of Anesthesia, 4th Edition, Stoelting, R.K. and Miller, R.,

p 119- 130, 2000)

-

Hobbs, W.R, Rall, T.W., and Verdoorn, T.A., Hypnotics and Sedatives;

Ethanol In, Goodman and Gillman's The Pharmacologial

Basis of Therapeutics,(Hardman, J.G, Limbird, L.E, Molinoff, P.B.,

Ruddon, R.W, and Gilman, A.G.,eds) TheMcGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.,

1996, pp. 364-367.

-

3Sno E. White The Preoperative

Visit and Premedication in Clinical Anesthesia Practice pp.

576-583 (Robert Kirby and Nikolaus Gravenstein, eds) W.B.

Saunders Co., Philadelphia, 1994

-

4John R. Moyers

and Carla M. Vincent Preoperative Medication in Clinical Anethesia,

4th edition (Paul G. Barash, Bruce. F. Cullen, Robert K. Stoelting,

eds) Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA, 2001

-

5Kathleen R.

Rosen and David A. Rosen, "Preoperative Medication" pp.

61-70 in Principles and Procedures in Anesthesiology (Philip

L. Liu, ed) J. B. Lipincott Company, Philadelphia, 1992

|