Medical Pharmacology Chapter 35 Antibacterial Drugs

First-Generation Cephalosporins

First Generation Cephalosporins: Audio Overview

|

|

|

|

|

|

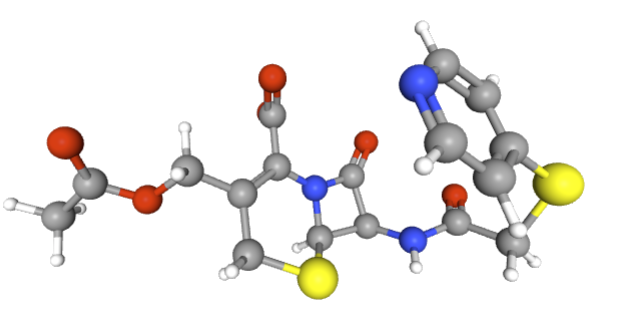

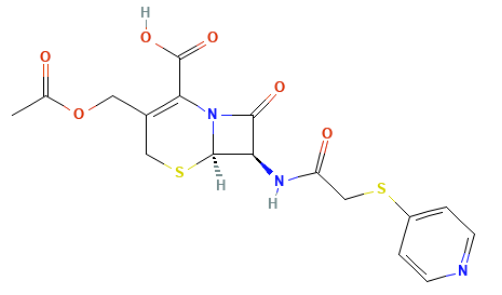

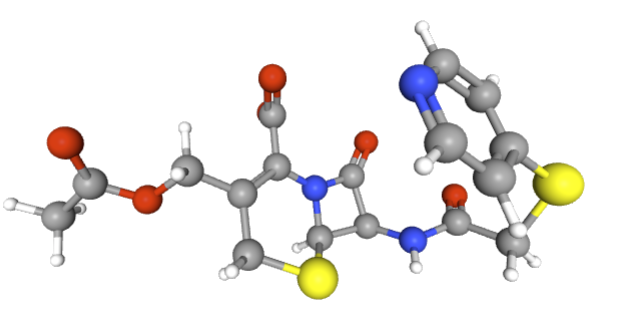

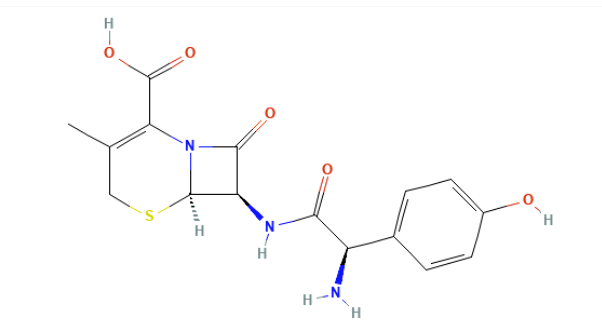

First-generation cephalosporins represent the pioneering class of cephalosporin antibiotics, introduced into clinical practice in the early 1960s.

These β-lactam antibiotics, an important advanced in antimicrobial therapy, were originally derived from the mold Acremonium (previously called Cephalosporium).

The first-generation cephalosporins include:

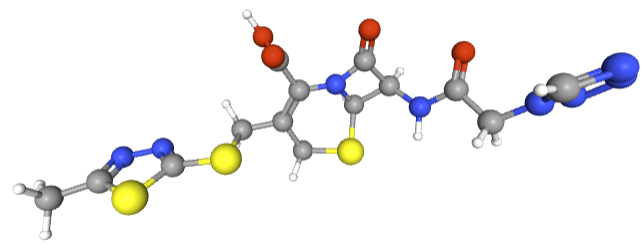

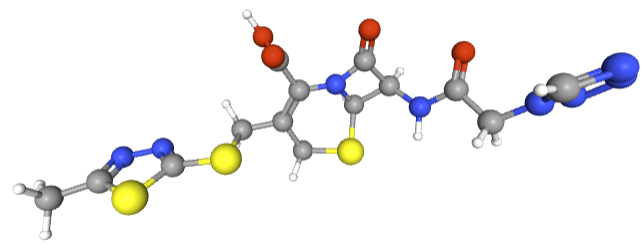

Cefazolin

|

|

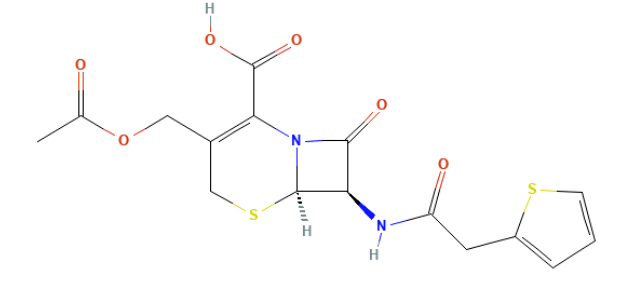

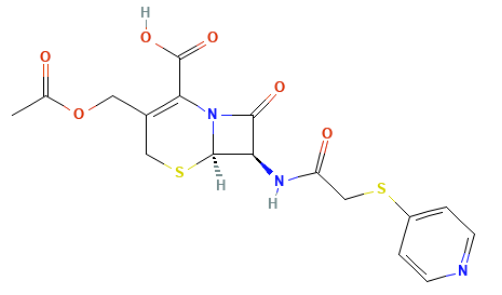

Cephalothin

|

|

Cephapirin

|

|

Cephradine

|

|

Cefadroxil

|

|

Cephalexin

|

|

Each of the agents above offer unique pharmacological properties while sharing a common mechanism of action.

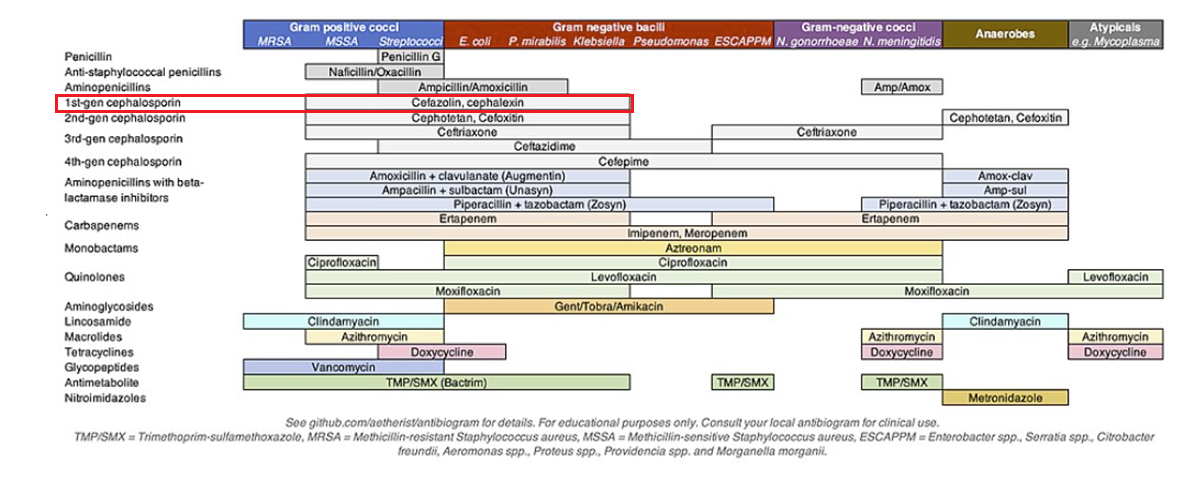

To facilitate classification of this antibiotic family, a "generation" system was developed.

This classification approach groups cephalosporins based mainly

on their spectrum of antimicrobial activity as well as when they

were introduced to the market.

First-generation cephalosporins are defined by their potent

activity against Gram-positive bacteria along with modest but

clinically important spectrum against a limited set of

community-acquired Gram-negative pathogens.

![]()

![]()

The principle involves selecting the narrowest-spectrum, most effective drug to treat the pathogen while minimizing damage to the microbiome.

The major drugs of the first generation include

parenteral formulations, such as cefazolin and cephalothin, and

orally administered drugs, including cephalexin, cefadroxil, and

cephradine.

|

![]()

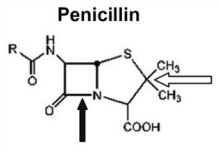

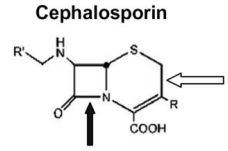

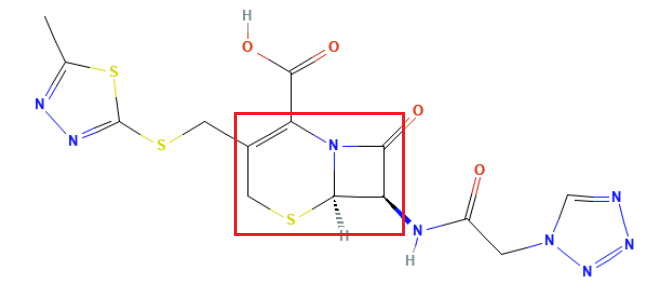

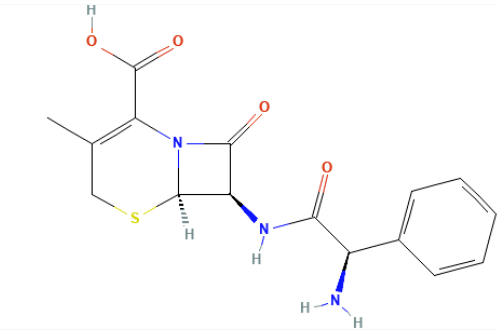

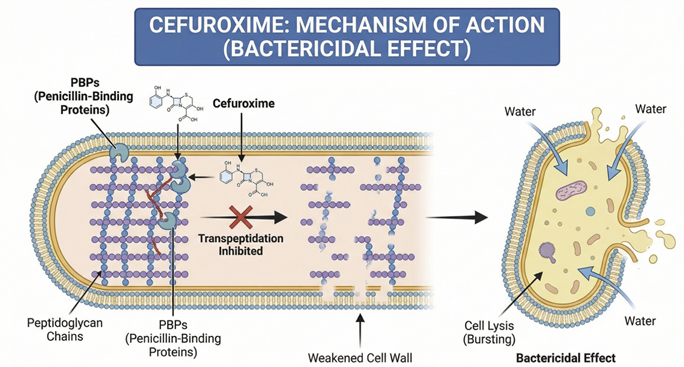

Like other β-lactams, they contain a β-lactam ring that binds to and inactivates penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs), which are the transpeptidase enzymes responsible for cross-linking peptidoglycan strands in the bacterial cell wall.9

By blocking the transpeptidation step, cephalosporins prevent peptidoglycan cross-linking, leading to a weakened cell wall and osmotic lysis of the bacterium.9 These drugs mimic the D-alanyl-D-alanine terminus of peptidoglycan precursors, irreversibly acylating the active site of PBPs.

The result is an inability of bacteria to maintain cell wall integrity, causing cell death which is a time-dependent bactericidal effect.

Staphylococcus aureus can acquire resistance by producing altered PBPs (e.g. PBP2a encoded by the mecA gene) that have low affinity for β-lactams .

![]()

Another resistance mechanism is bacterial production of β-lactamase enzymes that cleave the β-lactam ring; first-generation cephalosporins are susceptible to some β-lactamases produced by Gram-negatives, limiting their spectrum.8

First generation drugs are

stable to

staphylococcal penicillinase, allowing them to kill

methicillin-susceptible S.

aureus (MSSA) where penicillin G would be inactivated.9

September, 2025

|

|

This Web-based pharmacology and disease-based integrated teaching site is based on reference materials, that are believed reliable and consistent with standards accepted at the time of development. Possibility of human error and on-going research and development in medical sciences do not allow assurance that the information contained herein is in every respect accurate or complete. Users should confirm the information contained herein with other sources. This site should only be considered as a teaching aid for undergraduate and graduate biomedical education and is intended only as a teaching site. Information contained here should not be used for patient management and should not be used as a substitute for consultation with practicing medical professionals. Users of this website should check the product information sheet included in the package of any drug they plan to administer to be certain that the information contained in this site is accurate and that changes have not been made in the recommended dose or in the contraindications for administration. Advertisements that appear on this site are not reviewed for content accuracy and it is the responsibility of users of this website to make individual assessments concerning this information. Medical or other information thus obtained should not be used as a substitute for consultation with practicing medical or scientific or other professionals. |